Behind The Scenes II

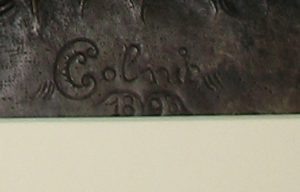

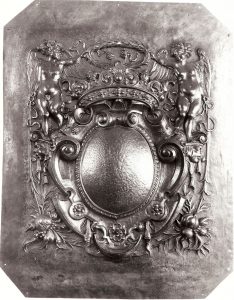

This piece, entitled “Escutcheon”, by master blacksmith Cyril Colnik (1871-1958) is one of the finest examples of repoussé that I have ever seen. It is made from 16 gauge (1/16″ thick) iron, demonstrating the elastic nature of iron.

This piece, with it’s cherubs, laurels, ribbons, along with a crown with precious stones, fruit of the harvest, and all encompassing a mighty shield, is part of the permanent collection of Colnik’s work at Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum in Milwaukee. It was first viewed at the Columbian Exhibition of 1893 in Chicago.

I do not have the exact dimensions, but it is approximately 20″ x 24″. It is the only known piece of ironwork signed by Cyril Colnik, not including his tools. It is curious that he often signed many of his tools, but not the work that the tools produced.

The piece was made by placing the sheet on a thick bed of “pitch”, which is as peanut brittle when cool, but when lightly heated, becomes more like stiff clay. It works well to back the material so that small punches may shape the metal without heavily distorting it.

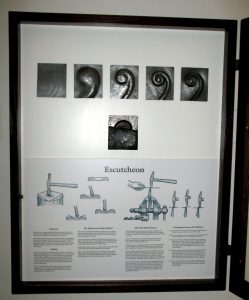

Blacksmith Tom Latané (Pepin, WI) produced a fine story board, as well as an appropriate cabinet to display this piece for Villa Terrace. The story board depicts how a form progresses using a bed of pitch, along with dozens of tiny punches.

The images below (from Tom’s storyboard) show the individual progressions of a scrollform more closely.

This first image shows the backside of the sheet, with some of the pitch cut away so you can see the shape that was produced.

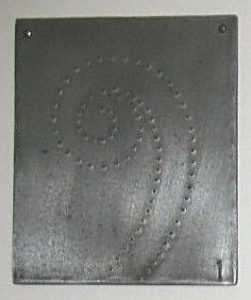

The first step is to establish the shape on the sheet. Tom used a center punch, putting light dimples in to outline the form.

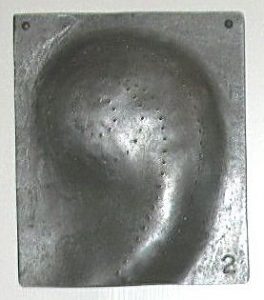

The next step is to sink the form, in either lead, or a wood stump, approximating the general shape, and also creating a raised form from which the scroll can be detailed.

The outline is then better defined.

Next, the scroll’s shape is further refined.

Finally, the lines are further worked and planished, creating a crispness to the form.

No matter how much care is taken, the piece will eventually break away from the pitch. This is caused by the metal shrinking as the work progresses.

The workpiece is then removed from the platen, and then warm, gooey pitch is re-applied to the back of the workpiece, as well as the platen. (A platen is a steady and secure block on which to mount the workpiece.)

Such is the process Colnik used to make this piece.

The piece has been mounted in a cabinet, allowing the veiwer to open the cabinet, and then study the backside where the pitch contacted the piece. Below are some images showing the back of “Escutcheon.”

The next image is the lower left corner of the piece.

Below is the upper left, showing one of the cherubs.

Here is the other cherub, in the upper right corner.

Below is the lower right hand corner.

The depth of the features in this piece is incredible. Colnik obtained maximum stretch from the material.

It is also good to point out here that one needs to anneal the workpiece as it workhardens while shaping. If it is not annealed from time to time, the piece will crack and split.

There are at least five or six pin-hole sized areas where Colnik did break through the metal. It is to be expected with such an undertaking as this to break through several times.

Finally, here is the piece, as mounted in Tom’s cabinet, along with an enlargement of the handle to open the cabinet.

As you can plainly see, Tom Latané is obviously a fine craftsman in his own right.

Below is a B+W image taken by a professional photographer back in 1993.

Note: To see another one of Colnik’s works from the backside, view this post: Behind the Scenes I.

……Dan Nauman

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.”……..Aristotle, Philosopher